When it comes to cleaning up the Coosa River, Georgia’s environmental regulators are behind the times…by about a decade.

Plant Hammond on the Coosa River near Rome. This coal-fired power plant as much as 600 million gallons of water from the Coosa each day–about the same as what all of metro Atlanta uses in one day.

Georgia’s Environmental Protection Division (EPD) recently issued a draft wastewater discharge permit for Plant Hammond, a massive 60-year old coal-fired power plant sitting on the Coosa River near Rome. It comes five years after it was supposed to be reviewed and ten years since the agency last updated it.

For a decade EPD’s inaction has prevented citizens from objecting to Plant Hammond’s impact on the river and delayed action to reduce pollution coming from the plant.

In those ten years we have learned a lot about the hazards associated with coal-fired power plants – including the impacts from their massive water withdrawals, hot wastewater discharges and toxic releases. This knowledge has prompted the federal government to enact new rules that force the modernization of outdated power plants like Hammond.

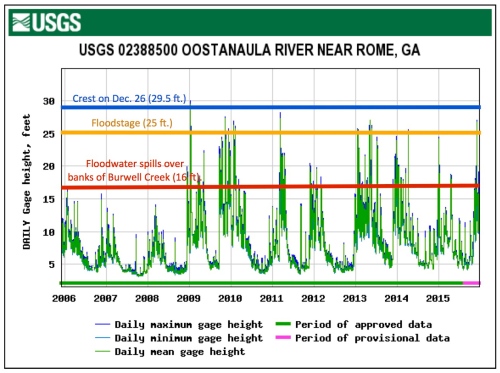

But the new permit that EPD plans to issue for Plant Hammond just kicks the can further down the road. It gives Georgia Power several years longer to comply with new regulations meant to curb the discharge of toxic metals to the river. And, its plan for reducing the hot water coming from the plant remains essentially the same as it has since 2007, meaning the plant can continue withdrawing up to 600 million gallons of water a day from the river.

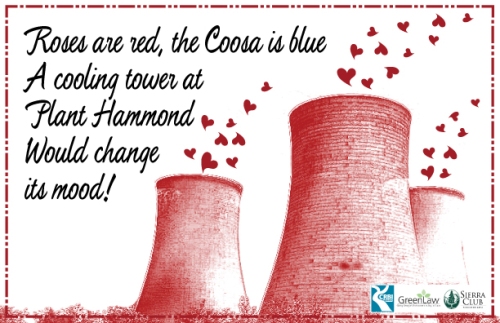

All the Coosa needs is love…and a cooling tower!

That massive withdrawal, by the way, may kill more than 30,000 fish each year, and millions more fish larvae as they become trapped against the intake screen or sucked through the water intake system.

Installing a cooling tower at the plant would resolve these issues caused by Plant Hammond’s withdrawals and hot water discharges. In fact, as far back as 2004, EPD was poised to require this very measure. But, here we sit, more than a decade later, doing business as usual.

It gets even worse. Stored along the banks of the Coosa at Plant Hammond in ponds are large volumes of industrial wastewater and tons of coal ash waste, containing known toxins like mercury, arsenic, and cadmium. In the next few years, Georgia Power plans to drain and treat the water from these enormous waste ponds, potentially causing substantial amounts of heavy metals to be dumped into the Coosa.

Through this permit, EPD could and should set limits on how much toxins can be released to the river from these ponds, but the agency is not doing that. Nor is it allowing these coal ash dewatering plans to be reviewed by experts outside of EPD. Instead, Georgia Power and EPD will settle on a plan to drain the ash ponds amongst themselves. It’s what you might call a “gentleman’s agreement” between EPD and Georgia Power.

That such a cozy relationship exists between the two is no surprise. During the recent General Assembly session, when legislators introduced bills to enact stronger rules on handling coal ash and dewatering of coal ash ponds, those efforts were quickly shot down.

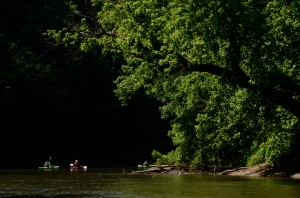

To restore the Coosa and its fishery, EPD must issue a pollution control permit for Plant Hammond that reduces the facility’s hot water discharge and massive water withdrawal.

Instead, Rep. Lynn Smith (R-Newnan), who chairs the House Natural Resources Committee, called a special meeting to “inform” legislators about, as she said, “what our state agency is doing and what our good corporate citizens, such as Georgia Power, are doing” in regards to coal ash.

EPD and Georgia Power then proceeded to paint a rosy picture of coal ash in Georgia. No opportunity was provided for anyone else to inform the legislators.

On April 12 at 7 p.m. at the Rome-Floyd ECO Center, citizens will finally have the chance to inform EPD. After a decade of being muzzled, those who care about the Coosa speak up and demand that the state do more to protect our drinking water and our swimming and fishing holes.

Jesse Demonbreun-Chapman

CRBI Executive Director & Riverkeeper

April 9, 2017